UN Plastics Treaty Falters as World Struggles to Break Free from Plastic

From August 5–15, 2025, government delegates, scientists and civil society representatives reconvened in Geneva to resume the fifth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC-5.2), tasked with developing the world’s first legally binding treaty on plastics pollution. Hopes were high in 2022, when the international community voted for Resolution 5/14—an ambitious global agreement addressing the full life cycle of plastics, from production and design to disposal. But by the close of INC-5.2, talks had collapsed, exposing deep power struggles that continue to shape the process. More than 100 countries, including many developing nations and the European Union, pushed for binding limits on plastics production, but entrenched political and economic interests prevented the world from addressing the crisis at its source.

The Plastic Crisis in Numbers

- More than 462 million tons of plastic are produced globally each year.

- 9–14 million tons of plastic enter the ocean annually.

- Of the 8.3 billion tons of plastics ever made, half has been produced since 2010.

- Only 9% of plastics are recycled; the rest is landfilled, incinerated, or left to pollute ecosystems.

- Without action, production could rise 70% by 2040 to 736 million tons/year, while the overall recycling rate will remain below 10%.

- Global plastic waste could reach 1.7 billion tons by 2060, carrying an estimated cumulative cost of $281 trillion.

- Seven countries, including China, the U.S. and Saudi Arabia, produce two-thirds of the world’s plastics.

Health and Environmental Impacts of Plastic Pollution

At a workshop hosted by the Center for Earth Ethics (CEE) and Beyond Plastics in March 2025, the host, Rev. Kathryn Beilke, highlighted that we have seen an “onslaught of production and plastics incursion into literally every aspect of our lives.” And indeed, plastics are everywhere. We eat and drink from plastic containers, wear plastic clothing and plastic makeup, sleep on plastic bedding, and clean our teeth with plastic toothbrushes.

Since their invention less than 200 years ago, plastic waste has littered every corner of the Earth. Most plastics are not recyclable and take anywhere from 20 to 500 years to decompose, and even then, they never fully disappear; they just break down into smaller and smaller particles.

Researchers have detected microplastic particles in clouds, altering rainfall cycles and further degrading into greenhouse-gas-emitting compounds. Plastics have been found in snow on top of the world’s tallest mountains and in sediment on the deep ocean floor, accelerating biodiversity loss and climate change. Animals ingest microplastics, suffering internal harm and experiencing behavioral modifications.

We have seen an onslaught of production and plastics incursion into literally every aspect of our lives.

Rev. Kathryn Beilke

Plastics injure people too. Recent research shows that we now ingest or inhale 78,000 – 211,000 microplastics every year, through food, water and air, building up in the heart, lungs, liver, and even brain tissue and joints. The chemical additives in plastics are known to cause cancer and are linked to a higher risk of heart disease, stroke or death. Particles can also damage reproductive health—they have been detected in placenta, breast milk and semen, raising profound intergenerational concerns. The problem is so pervasive that the World Economic Forum has ranked plastic pollution among the top 10 risks with the most severe expected impacts over the next decade.

Advocacy groups including WWF, the #BreakFreeFromPlastic Coalition and CEE have demanded urgent global action on plastics. Faith communities have further raised the alarm about the deeper ethical and spiritual dimensions of the plastic crisis. In a statement drafted ahead of the INC-5.2 negotiations, the UN Environment Programme’s Interfaith Working Group on Pollution—of which CEE is a member—urged governments to recognize the “sacredness of Earth’s systems” and called for ambitious, coordinated action.

“Plastic pollution is not only an ecological crisis—it is a spiritual and moral one. It poisons lands and waters, harms health, and disproportionately burdens low-income communities, waste pickers, Small Island Developing States, and Indigenous Peoples.”

Plastics, Fossil Fuels and Justice

As CEE has emphasized, the plastics crisis is inseparable from the fossil fuel economy: more than 99% of plastics are derived from petrochemicals. As the world transitions to cleaner energy, the fossil fuel industry is doubling down on petrochemical expansion to sustain profits. Major companies, including BP, Chevron, ExxonMobil, Shell and China National Petroleum, account for over half of global naphtha sales—the chemical feedstock for producing plastics. ExxonMobil is now the world’s leading producer of single-use plastic waste.

The resulting environmental injustice is all too familiar: plastics production facilities are “literally poisoning the people living near them,” Rev. Beilke explained. In the U.S., petrochemical plants are concentrated along the Gulf Coast and in “Cancer Alley” in Louisiana—communities disproportionately burdened by air pollution and rising health risks. Globally, manufacturers often site facilities in regions where power imbalances make resistance difficult, sacrificing local health and safety under the banner of jobs and prosperity. In this way, the plastics economy thrives by exploiting the same fractures that have long divided communities and nations.

The Path to a Global Treaty

The international community agrees on the need for urgent action to curb plastic pollution. In March 2022, the UN Environmental Assembly (UNEA) met in Nairobi, Kenya, to debate the global plastics crisis. In a historic move, 175 nations adopted Resolution 5/14, asking the UN Environment Programme to bring together an Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) to develop a global, legally-binding treaty to address plastics pollution across its full lifecycle. Negotiations began later that year, aiming to conclude by the end of 2024.

However, at their fifth round of talks in November 2024 (INC-5.1), deep divisions persisted as negotiations could not resolve several key issues. Countries failed to agree on whether the treaty should tackle the entire plastics value chain, including production and toxic chemicals, or focus narrowly on waste management. Key disagreements also centered on the production of primary polymers and financing mechanisms.

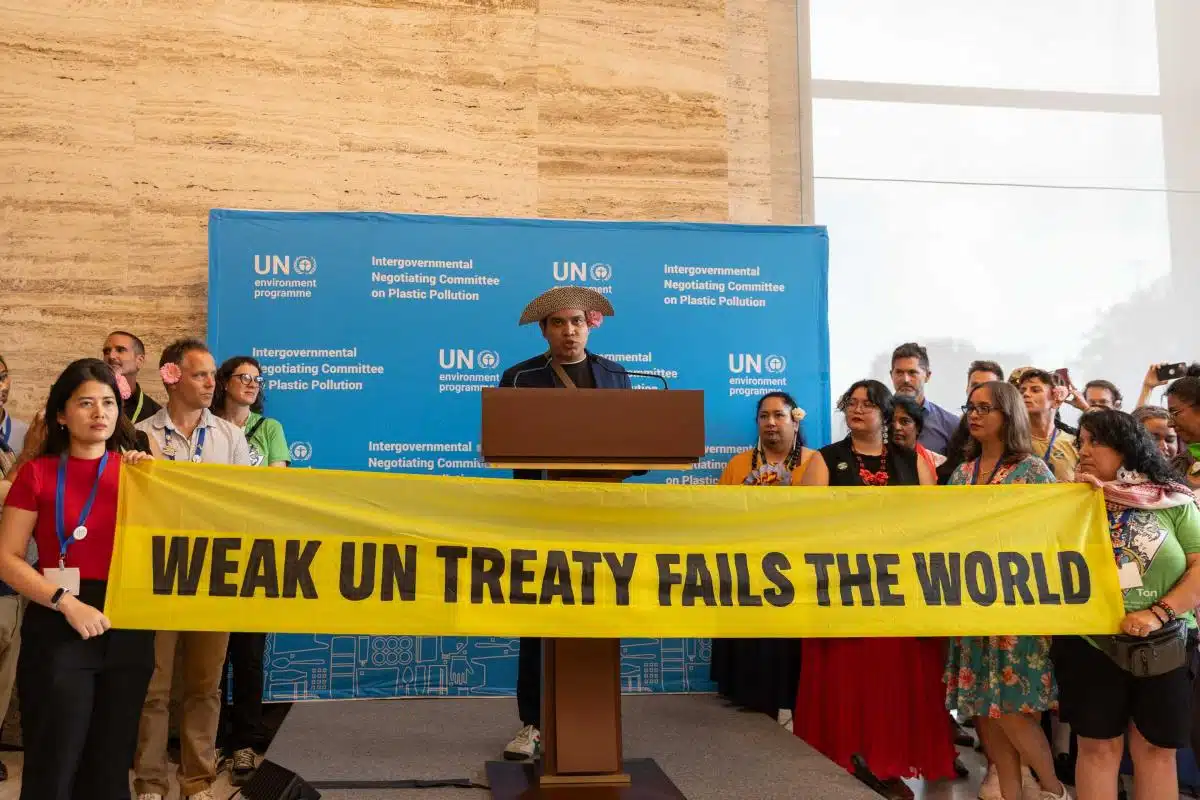

After failing to reach an agreement, delegates reconvened in Geneva this August. INC-5.2 drew more than 2,600 participants, including 1,400 delegates from 183 countries, nearly 1,000 observers from more than 400 organizations and around 70 ministers. After two compromise drafts were rejected by opposing blocs, the talks collapsed in the early hours of August 15, and the chair adjourned the session without an agreement once again.

With petrochemical lobbyists shaping policy from the inside, these negotiations showed plainly how profit, not planetary survival, still drives the global response to plastic pollution.

Rosie Semlyen

What Went Wrong

While UNEA Resolution 5/14 was negotiated largely by environment ministries, INC-5.2 was led by energy ministries, shifting the framing from an environmental crisis to an economic treaty. Ninety-six countries called for urgent measures to curb unsustainable production, but major oil-producing states—backed by the U.S. and Russia—consistently resisted provisions to limit plastics at their source, insisting instead on a treaty focused on waste management.

The U.S. government, in particular, actively undermined progress. Ahead of INC-5.2, U.S. officials sent letters to several countries, warning them not to support “impractical global approaches such as plastic production targets or bans and restrictions on plastic additives or plastic products.”

Meanwhile, industry influence was unprecedented: a Center for International Environmental Law analysis found that a record 234 fossil fuel and chemical industry lobbyists attended INC-5.2, with 19 embedded directly within national delegations. With petrochemical lobbyists shaping policy from the inside, these negotiations showed plainly how profit, not planetary survival, still drives the global response to plastic pollution.

Process disputes further stalled progress towards an agreement. Countries argued over whether the treaty should include globally binding controls or rely on voluntary national plans, and whether decision-making should allow for voting or require strict consensus. While 120 countries supported a voting mechanism to prevent deadlock, Brazil, Russia, India and China refused, insisting on consensus-only rules—a position that effectively gave fossil fuel-aligned states veto power over stronger measures. By the close of negotiations, with the draft text marked with almost 1,500 “brackets”—parenthesis placed around text that has not yet been agreed upon—there was “no way they could proceed with consensus.”.

By the close of INC-5.2, frustration ran high among negotiators and advocators alike. UN Secretary General António Guterres expressed “deep regret” that negotiations were unable to reach an agreement. Similarly, Erin Simon, Vice President and Head of Plastic Waste & Business at WWF, spoke to the collective mood on August 15:

"It’s deeply disappointing to leave Geneva without meaningful progress once again. This breakdown in negotiations means the plastic crisis will continue unchecked, while the world waits for the urgent action it so desperately needs."

Next Steps for the Treaty

Although INC-5.2 ended without agreement, negotiations continue. A date for the next round has yet to be announced, but the mandate stands: the world will have a global, legally binding treaty on plastic pollution. What remains at stake is the strength of that treaty and whether it addresses the crisis at its source. As CEE and the multifaith coalition have stressed, we cannot recycle or clean our way out of this crisis. So long as plastic production continues to grow unchecked, pollution will keep rising.

The Multifaith Working Group on Pollution outlined the following priorities for the treaty:

- Limit plastics at their source. Unchecked growth locks in climate damage and environmental injustice.

- Eliminate single-use and harmful plastics.

- Fund waste management and cleanup through a dedicated global fund.

- Invest in circular and reuse systems.

- End subsidies for plastic production.

- Guarantee a just transition for workers and frontline communities.

- Create fair and predictable financing mechanisms.

- Ensure inclusive and transparent governance, with safeguards against industry interference.

At the next meeting of INC, CEE and the Multifaith Working Group call on negotiators to “act with courage, compassion and a commitment to justice, choosing creation over convenience, justice over profit and the well being of all life over short-term interests.” Without confronting the plastics crisis at its source, the cycle of pollution, injustice and ecological harm will continue.

All photo are courtesy of IISD Earth Negotiation Bulletin/Kiara Worth and can be found here.

Rosie Semlyen

Rosie Semlyen is a research and policy associate at Center for Earth Ethics.