Top UN Court Sets New Ethical Climate Precedent in International Law

On July 23, 2025, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) delivered a groundbreaking advisory opinion on climate change. For the first time, the United Nations’ top court unanimously affirmed that states are legally obligated under international law to take meaningful action to address the climate crisis, and that failure to act on climate protection could violate international law.

While advisory opinions are not legally binding, they carry significant legal and moral weight. This marks a major moment in the growing effort to transform climate accountability from voluntary pledges to enforceable obligations and offers a new tool for accountability. It also reflects the calls of Indigenous communities, youth movements and climate vulnerable states, who have long insisted that climate justice is a legal and ethical imperative.

The Long Road to Legal Recognition

The world has understood the basic mechanisms of climate change for well over a century. Scientists John Tyndall and Svante Arrhenius first identified the warming effects of carbon dioxide in the 19th century. Yet it was not until the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro that international political action began to take shape. There, representatives from 178 countries, including more than 100 world leaders, adopted five major documents, including the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). These agreements finally acknowledged the pressing dangers posed by climate change, becoming the cornerstone of international climate cooperation.

Since then, global negotiations have continued under the UNFCCC, which requires signatory countries to meet each year at the Conference of the Parties (COP), with the meetings held in different world regions annually. The 1997 Kyoto Protocol was the first major treaty to establish emission reduction targets for industrialized countries, and the 2015 Paris Agreement set a goal to limit global temperature rise to well below 2°C, striving for 1.5°C. But crucially, these agreements rely heavily on voluntary action and lack enforcement mechanisms.

Today, atmospheric CO2 levels have reached a new record of 430 parts per million, and emissions are still rising. 2024 marked the first time the world broke 1.5°C of warming above pre-industrial levels. While this does not mean the long-term goal is out of reach, scientists warn that we could hit this limit in as little as three years. Without binding consequences, many countries have fallen short of their UNFCCC pledges. As the climate crisis worsens, the need for accountability in international climate policy has never been more urgent.

As the climate crisis worsens, the need for accountability in international climate policy has never been more urgent.

Clara Chavez-Ives & Rosie Semlyen

Grassroots Origins

Responding to insufficient global action to reduce emissions, a group of Pacific Island law students sparked what has now become one of the most significant legal actions in climate history. After a classroom discussion in 2019, 27 students from the University of South Pacific in Vanuatu founded the Pacific Island Students Fighting Climate Change (PISFCC) and decided to pursue the ambitious idea of asking the world’s highest court to issue an advisory opinion on climate change. While bold, they were not the first to seek an advisory opinion on climate damage. In 2011, the Pacific Island nation of Palau urged the UN General Assembly to take the issue to the ICJ, but the U.S. pushed back, claiming the effort might disrupt the lead-up to the Paris Agreement.

Though an advisory opinion has no binding force, it can be an instrument of preventive diplomacy and contribute to the clarification of international law. An opinion on states’ obligations to address climate change would clarify legal questions that have haunted climate negotiations for decades. It could have huge implications for climate change litigation, developing domestic law, and adjudicating international, regional and domestic disputes.

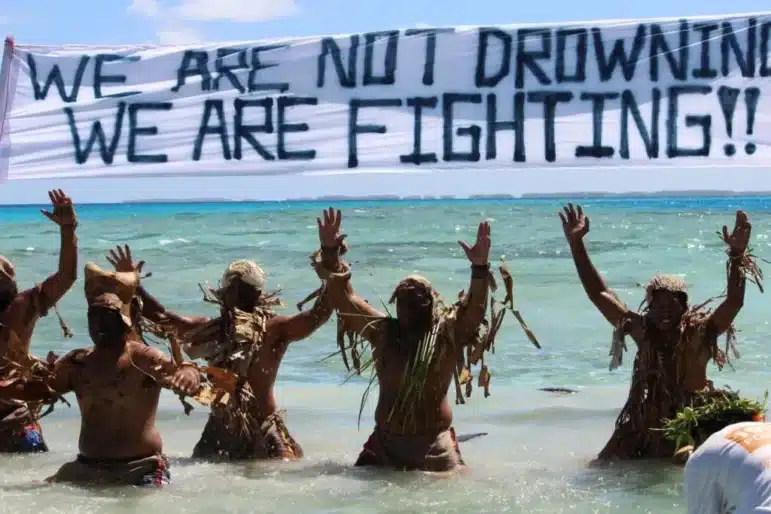

Over the years, the students’ campaign faced significant resistance from major GHG-emitting countries. However, it resonated worldwide. As the campaign grew, PISFCC collaborated with global youth, forming the World’s Youth for Climate Justice (WYCJ). Their calls to action were heeded by the government of Vanuatu—a small island developing state (SID) in the Pacific that the UN ranked as the country most prone to climate disasters—which supported the effort by managing the diplomatic aspects within the UN system.

This work progressed on March 29, 2023, when the UN General Assembly supported the PISFCC’s campaign by adopting Resolution 77/276, the “Request for an advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice on the obligations of States in respect of climate change,” with overwhelming support from more than 130 countries. When the hearings opened in 2024, the Court received a record 91 written submissions from states and civil society organizations. It heard testimony from Indigenous leaders and frontline communities, which described climate change as a threat to their lands, food, water and livelihoods, as well as cultures, homelands and spiritual lifeways.

Ilan Kiloe, who spoke for the Melanesian Spearhead Group, described the deep relationship between the region’s people and the land, warning of the risks posed by weak climate action:

We are “placepersons,” which means we are the places; we are the landscapes, we are the waters, and we are the soils, the stones, and we are the flora and the fauna, we are the weather, the seasons, and the spirits of our ancestral territories. Yet now, across our sea of islands, anthropogenic climate change has imperilled our peoples’ physical survival and ripped apart the integral relationships between people and place that grounds our very existence. Simply put, climate change has unravelled the fabric of our lives.

Cynthia Houniuhi, PISFCC president, detailed how, for her community, the land is precious:

Land is our mother, a living, timeless plane where generations past, present and future converge, interconnected and sustained in an unbroken cycle of life. It is upon our land that our values and principles are rooted, preserved and transmitted across generations. Climate change is undermining our ability to uphold this sacred contract. My people’s land of Fanalei is nearing a critical point, on the verge of being completely engulfed by the rising seas. Without our land, our bodies and memories are severed from the fundamental relationships that define who we are.

These stories, among the many oral and written testimonies submitted to the ICJ, are a powerful reminder of the growing costs of climate change and insufficient action.

A Historic Opinion

On July 23, 2025, the ICJ delivered its opinion. In a major milestone for international law, the Court stated unequivocally that climate change is an urgent concern for human rights, justice and international peace and security, as well as a major threat to climate and environmental stability.

The Court declared that parties to the UNFCCC are obligated “to adopt measures with a view to contributing to the mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions and adapting to climate change.” Furthermore, Annex I countries—primarily developed countries and some “in transition” economies—have “additional obligations” to lead the fight against climate change and reduce emissions. The ruling states that all signatory countries must work together to achieve the UNFCCC’s goals, meaning that parties to the Paris Agreement must act to achieve the 1.5°C temperature goal. Likewise, they are obligated to comply with the Kyoto Protocol. Other environmental agreements mentioned in the Court’s ruling include the Vienna Convention, the Montreal Protocol, the Convention on Biological Diversity, the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification, and the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. Parties must “prepare, communicate and maintain successive and progressive nationally determined contributions”—a particularly relevant inclusion since many countries have yet to submit their updated emissions reduction goals before the upcoming UNFCCC climate conference (COP30) this November in Belém, Brazil.

[The ruling] affirms a simple truth of climate justice: those who did the least to fuel this crisis deserve protection, reparations and a future.

Vishal Prasad

The ICJ’s opinion went further, clarifying that all nations, even those that are not party to such agreements, are bound by “customary international law” to prevent environmental harm and must act with “due diligence” and “all means at their disposal” to address climate risks and cooperate accordingly. This specification is significant given recent alarms about the breakdown of multilateralism, as the U.S. and other major countries have stepped back from international agreements, with the Trump administration initiating the process to leave the Paris Agreement (for the second time) earlier this year.

Most crucially, the ICJ found that countries that fail to comply with their obligations can be held responsible for “internationally wrongful acts,” requiring them to: cease the violations (i.e., curb emissions), guarantee non-repetition of these actions, and to provide “full reparation to injured States in the form of restitution, compensation and satisfaction,” assuming a causal link can be drawn. The final point provides a framework for countries to pursue climate reparations claims, whereby high-emitting states would be responsible for transferring funds to low-emitting states that suffer the greatest impacts of climate change.This is a major victory for SIDS, with PISFCC Director Vishal Prasad explaining how “it affirms a simple truth of climate justice: those who did the least to fuel this crisis deserve protection, reparations and a future.”

The Growing Legal Consensus

The ICJ’s opinion builds on an emerging body of international legal opinions that frame climate change as a human rights and justice issue. The first advisory opinion on states’ obligations to address climate change from an international tribunal came in May 2024, when the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) stated that countries are obligated to reduce their emissions and to work together. This opinion set a high standard of due diligence, given the serious threats that emissions pose to marine environments. In early July 2025, Latin America’s top human rights court, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR), released a unanimous advisory opinion that affirmed the ongoing climate emergency and that states must cooperate to protect human rights. Additionally, in May 2025, a coalition of NGOs requested an advisory opinion from the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights (AfCHPR) addressing, among other things, the protection of vulnerable groups, inter-state cooperation, intergenerational responsibility and reparations. Together, these cases signal a growing recognition that “the environment is the foundation for human life, upon which the health and well-being of both present and future generations depend.” The Court considers that the “protection of the environment is a precondition for the enjoyment of human rights,” therefore, states have a legal obligation to address climate change.

Implications for Climate Action and Justice

Though the ICJ opinion is not enforceable like a national court ruling, it carries powerful symbolic weight. It can shape legal strategies and negotiations, providing a solid foundation for climate litigation in national courts and strengthening calls for reparations and financing.

The ICJ’s advisory opinion will likely influence events at COP30 in Brazil later this year. Firstly, it confirms that parties are obligated under the Paris Agreement to prepare progressive nationally determined contributions (NDCs), or climate pledges. Previously, most countries have shirked this responsibility, with 95% missing the February 2025 submission deadline. Hopefully, this newly outlined clarification of international law will push countries to achieve the new September 2025 deadline. Secondly, the advisory opinion may encourage negotiations on historically tense topics, like climate finance. As Vanuatu’s Minister of Climate Change Ralph Regenvanu, said during a seminar following the ruling, “there are arguments—unlawful and illogical arguments—that can’t be made anymore.”

One major area of relevance is “loss and damage”—a term encompassing the economic, cultural, social and environmental harms caused by climate change. It includes permanent impacts, like the loss of life or land, as well as repairable damages, like most physical structures. As with the request for the ICJ’s advisory opinion, Vanuatu, along with other developing nations and SIDS, has long pushed for loss and damage, first raising the issue at the UN in 1991. Over three decades later, at COP28 in 2023, UN member states agreed to establish a dedicated Loss and Damage Fund, where wealthier countries—historically responsible for releasing more emissions—contribute to offset the losses and damages faced by less wealthy, less culpable and more vulnerable nations. Initial analysis provides hope that the ICJ’s opinion, particularly the inclusion of human rights law and the ability for injured states to seek reparations, will spur progressive action to finance this mechanism adequately and ensure that high-emitting countries meet their responsibilities under the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement.

It is impossible to quantify or resurrect the traditions and cultural artifacts that have already been lost to climate change, and no opinion can erase the pain of communities that have had to flee their homelands and resettle elsewhere (sometimes multiple times). Still, the ICJ’s bold statement is a call to end the greenhouse gas emissions driving this loss and damage. The Court has clearly defined that all countries must address climate change and “cannot escape responsibility simply because they aren’t the only nation to blame.”

Although ICJ opinion has sparked hope among climate justice advocates, it is unlikely to have a major impact on the U.S. Still, it may “embolden” state and local governments working on climate action. Korey Silverman-Roati, a senior fellow at the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, noted that the impact on cases in the U.S. will be small since U.S. courts rarely cite the ICJ or acknowledge its authority. However, Silverman-Roati believes “the advisory opinion will likely instead influence other countries whose judicial systems give more weight to the ICJ, and influence the U.S. through the ruling’s use in international negotiations.” While the ruling still implicates the U.S. through “customary law,” the country has recently pulled out of the Paris Agreement and will no longer be bound by obligations for signatory parties. Additionally, to take polluting countries to international courts requires the consent of all parties involved, making it unlikely that the U.S. will be held to account.

The decision opens up new pathways for legal redress and offers a moral compass for international climate action by insisting on our shared obligation to protect life, uphold human rights and honor our sacred responsibility to future generations.

Clara Chavez-Ives & Rosie Semlyen

A Moral Mandate

At the Center for Earth Ethics, we understand climate change as both a policy challenge and a profound ethical and spiritual crisis. The ICJ’s opinion affirms that justice requires more than emissions targets and technological solutions. Rather, it demands accountability, reparations and care for the most vulnerable people, ecosystems and species. This declaration is a wake-up call for lawmakers and a boost for activists. The decision opens up new pathways for legal redress and offers a moral compass for international climate action by insisting on our shared obligation to protect life, uphold human rights and honor our sacred responsibility to future generations.

Clara Chavez-Ives

Clara Chavez-Ives is a research associate at the Center for Earth Ethics.

Rosie Semlyen

Rosie Semlyen is a research and policy associate at Center for Earth Ethics.