Alabama Voices: Two million Americans are in a water crisis; some of them are your neighbors

Catherine Flowers and George McGraw – Special to the Advertiser

Originally Published 9:00 AM EST Nov 22, 2019 to the Montgomery Advertiser

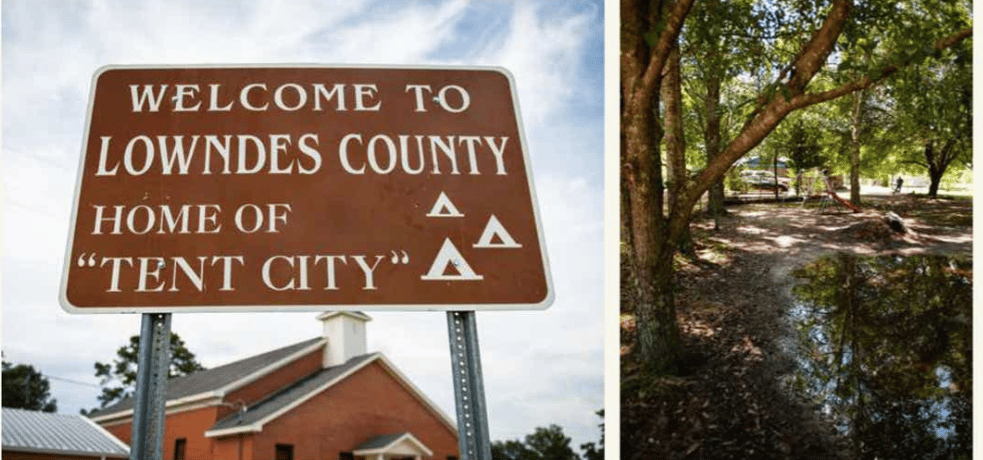

In the Black Belt running through Alabama and Mississippi, the dark, clay soil that gives the area its name is notorious for causing water woes.

Rainwater pools on the ground, because it can’t penetrate the dense soil. So does sewage.

In Bibb County, for instance, municipal wastewater is pumped into a lagoon where it should evaporate. When it rains, that wastewater overflows from the lagoon into people’s yards, spreading disease and smelling horribly.

In Lowndes County, only 20 percent of homes are connected to sewer systems.

But Bibb and Lowndes aren’t the only area in the Rural South – or the country – struggling to access reliable water and sanitation.

Recently two national non-profits, DIGDEEP and the US Water Alliance, released the first-ever report that pulls back the veil on America’s hidden water crisis. The report researchers visited Black Belt counties in Alabama and Mississippi, and five other regions across the US facing severe water access issues: the Four Corners area of the Southwest, the Central Valley of California, the Texas colonias, rural Appalachia, and Puerto Rico.

The report found something heartbreaking: there are at least two million Americans without hot and cold running water, a tap, shower, a working toilet, or basic wastewater service in their homes. That’s two million Americans who don’t have water to drink and cook with, or who have a toilet that simply empties through a PVC pipe into a puddle of sewage in their yard (if they have one at all).

This lack of basic water and sanitation access is causing a public health crisis. People repeatedly exposed to raw sewage are at greater risk for acute and long-term illness. Diseases once eradicated are resurfacing. A peer-reviewed study of residents in Lowndes County found 34.5 percent of participants tested positive for hookworm and other tropical parasites.

Perhaps the most disturbing thing uncovered by our research is that some parts of the country are actually going backwards. From 2000 to 2014 (the period with the last complete census data set) six states – Delaware, Idaho, Kansas, New Hampshire, Nevada, South Dakota – and Puerto Rico all saw increases in their populations without water and sanitation access.

This crisis affects Americans, who because of circumstances beyond their control, including geography, poverty, and discrimination, are unable to enjoy the same working taps and toilets most of us take for granted. The challenges vary by region and place. But across the country one thing holds true: this is a tremendous, invisible problem that our neighbors are often too ashamed to talk about. It is time to end the stigma and address it head-on.

First, America must begin measuring the water access gap. You can’t manage what you don’t measure. Previously, the Census Bureau asked whether homes had a working flush toilet, but recently removed the question. One of our simplest recommendations in the new report is for census to revamp the question on complete plumbing access to again include toilets, and add questions on wastewater services, water quality, and cost.

Second, federal, state and local government need to reimagine outdated water regulations that don’t account for the extreme circumstances some Americans are living in. They need to dramatically increase and restructure funding to help these families and their communities build systems that work for them – especially in remote locations where traditional, centralized infrastructure may be impossible.

Finally, we need to support local organizations doing the hard work of bringing clean water to their neighbors right now. The Center for Rural Enterprise and Environmental Justice and the Mississippi Worker’s Center for Human Rights are two of those organizations. Operating in Alabama, the Center for Rural Enterprise and Environmental Justice documents poverty and environmental crises, and works with affected communities to develop local solutions. The Mississippi Worker’s Center for Human Rights creates safer and healthier workplace conditions, including water access and sanitation, through education and training. The Center for Rural Enterprise and Environmental Justice seeks to improve access to clean air, water, and soil in marginalized rural communities by influencing policy, inspiring innovation, catalyzing relevant research, and amplifying the voices of community leaders, all within the context of a changing climate.

Solving this crisis is the right thing to do. To turn a blind eye to the suffering of millions is to deny their dignity. Fortunately, we are a resilient and creative nation, and with the right focus, resources, and partnerships we can close this water access gap in our lifetimes.

To read the full report and support groups like The Center for Rural Enterprise and Environmental Justice and Mississippi Worker’s Center for Human Rights, visit www.closethewatergap.org.

Catherine Coleman Flowers is Senior Fellow of Environmental Justice and Civic Engagement at the Center for Earth Ethics as well as the director of the Center for Rural Enterprise and Environmental Justice.

Learn More about Catherine’s work…

George McGraw is CEO of DIGDEEP.