A Call for Ethical Leadership on Deep Sea Mining

This summer, the future of the deep ocean took center stage. In June, global leaders, scientists and civil society convened at the UN Ocean Conference in Nice, France, and at the International Seabed Authority (ISA) negotiations in Kingston, Jamaica, where discussions around commercial deep sea mining gained momentum. As the ISA negotiations continue through July 25, 2025, governments and institutions are weighing how and whether to move forward with a practice that would open one of Earth’s last untouched ecosystems to industrial extraction. The choices they make now could shape ocean governance and planetary health for generations to come.

What Is Deep Sea Mining—And Why Now?

Deep sea mining involves harvesting metal-rich rocks—polymetallic nodules—from the ocean floor, often at depths of 4,000 to 6,000 meters. These nodules, especially abundant in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) of the Pacific Ocean, contain metals such as cobalt, nickel, copper and manganese, which are used in electric vehicle batteries, solar panels and other low-carbon technologies. They are estimated to have a market worth of between $8 and $16 trillion. Demand for critical minerals is expected to double by 2040, so proponents argue that mining deep sea nodules is essential to the energy transition and to meeting global climate goals.

However, these growth projections assume a continuation of current consumption patterns and technologies. They do not account for alternative pathways in which mineral demand decreases due to innovation, reuse and systemic change. In fact, battery technologies are evolving rapidly, with manufacturers moving away from cobalt and nickel in favor of more abundant alternatives. Lithium and graphite—key components in most batteries today—are not present in the nodules at all. Meanwhile, the potential for recycling and mineral reuse remains largely untapped, and innovations in public transportation and urban design could significantly reduce overall demand for battery materials.

In short, the path we take is not predetermined. The energy transition does not require deep sea mining, but proceeding without precaution risks irreversible damage to one of Earth’s most fragile ecosystems.

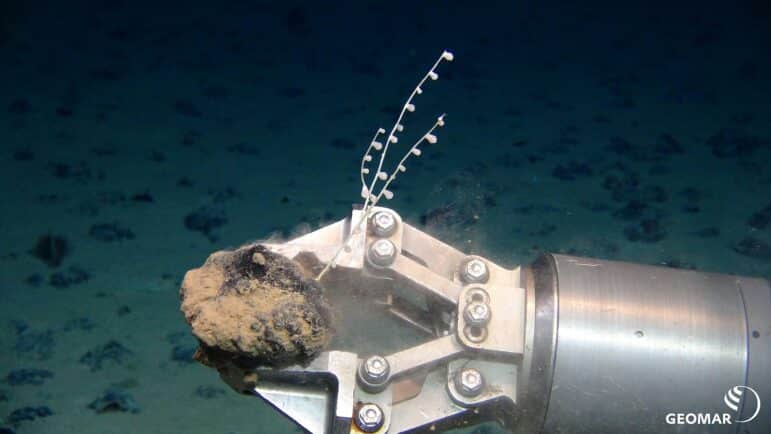

A polymetallic nodules on the seafloor of the Clarion Clipperton Zone (CCZ).

What We Stand to Lose

The deep ocean is the largest, and least understood, ecosystem on Earth. The seafloor in the CCZ, once thought to be barren, is now understood to support extraordinary biodiversity. A 2023 study estimates that more than 6,000 species may live in just this one region—and that’s likely an underestimate. These species thrive on and among the nodules themselves, which form over millions of years. Once removed, they cannot be replaced. Mining the deep ocean means intervening in ecosystems we barely understand. Without a baseline, we cannot even measure what is lost.

Beyond biodiversity loss, mining poses broader environmental and societal risks. Sediment plumes could travel far beyond mining sites, disrupting ocean food webs and threatening commercial fisheries. Indigenous Peoples, subsistence fishers and Small Island Developing States (SIDS) are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of deep-sea mining, as they are heavily reliant on marine resources for food and livelihoods. Hence, deep sea mining risks replicating extractive patterns in which the Global South bears the ecological risk while profits flow elsewhere.

Moreover, noise and light pollution would affect migratory species, and some scientists warn that mining activity could alter deep-ocean carbon cycles or release methane from seabed sediments. One recent paper even suggests that polymetallic nodules may play a role in producing “dark oxygen”—a previously unrecognized biological process that could reshape our understanding of life on Earth.

We currently have neither the knowledge nor the data required to assess whether humankind stands to lose more than we could gain if the ISA opens the deep ocean to industrial mining.

Deep Sea Conservation Coalition

Proceeding Without Protections

Mining companies are currently preparing to move ahead. The Metals Company, in partnership with Pacific Island nations such as Nauru and Tonga, is widely expected to submit the world’s first application to begin commercial deep sea mining. Crucially, this could occur before a binding international regulatory framework is in place.

The ISA, established under the 1994 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, is the principal body responsible for managing mineral-related activities in international waters and is tasked with establishing a regulatory framework that balances the exploration and exploitation of seabed minerals with the protection of the marine environment. However, the authority has not yet finalized its Mining Code, the set of rules that would govern full-scale deep sea mining. Negotiations are ongoing and contentious, with growing concerns about transparency, environmental oversight and conflicts of interest.

In the face of such uncertainty and the irreversible impacts mining could have on fragile deep-sea ecosystems, many scientists and advocates are calling for the application of the precautionary principle—the idea that, when an activity poses potential harm to the environment or human health, precautionary measures should be taken even if some cause-and-effect relationships are not fully established scientifically. Rather than proceed in the absence of robust safeguards, the precautionary principle urges restraint until there is sufficient knowledge, regulation, and accountability in place.

Applying this principle is especially important given the structural weaknesses in the current governance framework. Under UNCLOS, financial and other benefits derived from the deep ocean must be equitably shared among all states—especially SIDS, least developed countries and landlocked developing countries. To facilitate this, the ISA has “reserved” specific areas of the deep sea, which commercial mining companies can only access through sponsorship by a developing country. These arrangements are intended to support fair benefit-sharing, but serious questions remain about whether sponsoring states—often small and under-resourced—have the legal and technical capacity to provide effective oversight.

While international frameworks assign them clear responsibilities, enforcement remains a challenge. As we have seen in other contexts, from environmental treaties to humanitarian law, international legal obligations are not always treated as binding, and there are few mechanisms for enforcement—raising important concerns about accountability, especially when the stakes are as high as the future of the deep ocean.

The ethical question we now face is this: should we move ahead with industrial activity in a place we barely know, for resources we may not urgently need, using technologies and practices that have very few regulations?

Let this be a moment not of technological ambition and profiteering, but of moral clarity. The deep ocean has sustained life for millennia. We have a responsibility to return that gift with care.

Rosie Semlyen

A Time for Moral Clarity

In light of the risks and uncertainties, 37 countries have called for a moratorium, pause or ban on deep sea mining. More than 60 companies and financial institutions, including the European Investment Bank, Deutsche Bank and Standard Chartered, have pledged not to support it. Civil society coalitions, Indigenous groups, scientists and faith-based organizations are also speaking out, urging global leaders to act with caution and conscience.

The deep sea is not an open site of metals for companies to exploit—it is part of our shared planetary home. Under international law, its resources are designated as the “common heritage of humankind,” a reminder that they belong not only to those with the power to extract them, but to all people and to future generations. A robust ethical analysis also requires that we consider that ocean life has its own moral standing, apart from human claims on it. As Pope Francis put it in Laudato Si’, “We take these systems into account not only to determine how best to use them, but also because they have intrinsic value independent of their usefulness.” He adds that “consideration must always be given to each ecosystem’s regenerative ability in its different areas and aspects” (Paragraph 140). A full accounting of costs and benefits of deep sea mining demands that we weigh short-term gain against long-term planetary health, and that we exercise humility in the face of ecological systems we are only beginning to understand.

The moral imperative to accelerate the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy cannot be overstated, but that does not mean that the transition should happen without any precautions or boundaries. A just energy transition cannot be built on practices that cause needless and irreversible harm to ecosystems we cannot restore. If it is possible to make the energy transition without this destruction, we must forge that path. We cannot leave that determination to those who have financial incentives, but must instead convene a proper process for ethical decision making. We therefore urge global leaders, scientists and civil society to support a moratorium on deep sea mining until we have the scientific knowledge, regulatory safeguards and ethical frameworks to make truly informed choices.

Let this be a moment not of technological ambition and profiteering, but of moral clarity. The deep ocean has sustained life for millennia. We have a responsibility to return that gift with care.